I’m a sun that doesn’t burn hot. I’m a moon that never shows its face. I’m a mouth that doesn’t smile. I’m a word that no one ever wants to say.

I flew through Dulles Airport a few weeks ago. In and of itself, this fact is hardly momentous, given that I fly through there constantly. This time was different, though, because my walk from gate to gate involved a trip into the past and back to the scene of a crime.

There’s a little seating area in the middle of Concourse C that serves as the lobby for the people mover that shuttles travelers between terminals. I spent an afternoon sitting there two and a half years ago in the middle of a blizzard of epic proportions that had DC at a standstill and agonized over one of the most difficult decisions I’ve ever had to make. It was back when my father was in the hospital and I was shuttling back and forth from Colorado to the East Coast to be with him and help care for him. It was only a couple of weeks after his accident, and it was my second trip out to see him.

My father’s car rolled across that field at least nine times, and the impact had broken his back and neck in three places, crushed his sternum, and cracked all of his ribs. These injuries greatly compromised his ability to breathe. I had consented to intubating him and putting him on a ventilator shortly after his admission to the hospital because his blood oxygen levels were dangerously low. That meant medicating him into a coma with the intention that it only be necessary for three or four days in order to give his lungs time to recover enough to stave off pneumonia and gain the strength they needed to function on their own, at which time we’d bring him back around. Three days into the coma, the ICU doctors called me to tell me that my Dad had slipped down deeper than they’d intended — slipped completely through their fingers into a natural coma that medicine was no longer inducing and couldn’t break. They had pulled the drugs, and he wouldn’t wake up. No matter what they tried, they couldn’t get through to him. They were no longer in the driver’s seat, and there was no guarantee that anyone was home, much less ever coming back to us.

Now, it’s necessary to bring a player into this little drama that I’ve left out of the narrative up until this point in time, despite the fact that she was in nearly every scene. See, at the time of the accident, my father had a girlfriend — a widow his age he had met a few years before and had been living with for a little more than a year. Despite the fact that she was strange and ostentatious and a little too clingy and didn’t really seem his type, I had been supportive of the relationship and accepting of her. Dad seemed happy and I didn’t want to see him lonely. She wasn’t who I would have picked for my father, but hey, it was his life, so who was I to judge?

I had built a relationship with this woman, and she was the one who called me when the accident happened. Things went downhill and fast shortly after that phone call. When I arrived at the hospital directly from the airport hours later, she was livid about three facts: that my mother was at the hospital with me (she saw my mother as a threat despite the fact that my parents had divorced nearly 25 years prior), that my father had listed me as the primary decision-maker on his medical advance directive rather than her (an act that I have to say took a lot of guts on his part with her standing over him broken and bleeding in the ER), and that my father’s checkbook hadn’t come into the hospital with him. All she could do was worry that he hadn’t sent off a check to cover her homeowner’s insurance payment before the crash. The first issue I blew off entirely. The second I thanked my lucky stars for. The third I found odd and disquieting, to say the least, but I chose to back burner those concerns.

My brother arrived the following night and the two of us exchanged baffled and concerned looks across the hospital cafeteria table as we listened to this woman prattle on endlessly about that damn checkbook and numerous other inappropriate, non-Dad topics over dinner — mutual bells and whistles galore sounding in our heads as our eyes locked and carried on a silent conversation about the crazy woman right in front of her without her notice. Nonetheless, there the two of us were out in the cold rain the following day combing the crash site beside the highway for clues for what had happened to our father and searching the totaled car in the junkyard for that goddamn checkbook. Never found the fucking checkbook, but I sure as shit found a million other things that broke my heart and laid my hands on what was left of the bottle of rum that did the damage still in its brown paper bag complete with receipt inside my first minute in that Toyota. I paid the salvage man his fee to crush the car, and brother and I dragged ourselves back to our mother’s house defeated, chilled, and soaked. We were also equal parts confused and enraged. For her part, Mom took the bottle of rum from my hands, cursed my father under her breath, and held me. Later that night, she poured the cheap brown liquid down the drain and threw the bottle in to the woods back behind the house, listening as the glass shattered against a tree trunk in the darkness.

As the weeks wore on, I worked as hard to keep my family and Dad’s girlfriend informed of Dad’s condition on a daily basis as I did to care for Dad himself. If I wasn’t on the phone with a nurse or a doctor, I was on with one of the above — usually the girlfriend. She slowly began to take up as much of my time and effort as my father. It quickly became apparent that she was neither bright nor emotionally balanced and that I could never miss a phone call from the hospital lest they call her for consent as second in command per the advance directive. An ICU intern made the mistake of calling her first once, and she made a disastrously uninformed and emotional decision that almost killed my father. I was only able to undo it because a well-meaning nurse put her job on the line and called me behind the doctor’s back to tell me what was happening and give me the chance to fix it From then on out, I became obsessed with the phone and lived in fear of missing its ring.

A week after Dad slipped into the coma of his own making, the doctors asked for my consent to perform a CT scan of my father’s head to determine whether or not he was brain dead. Gotta tell you, that’s a call you never want to receive. I said yes and called the family and girlfriend to tell them what was happening. The calls then came in every twenty minutes from the girlfriend demanding a status update without regard for my own anxiety level. I took the dog for a walk in the park to try to calm myself, and still my phone rang. I left the park and drove to my boyfriend’s house where he was sleeping after his graveyard shift. I slipped quietly in the door, put the dog out onto the patio and crawled into bed behind him, put my arms around him, set the phone to vibrate, and tucked it into his hands so he would wake if it buzzed and screen any further calls. I slipped into a couple fitful hours of sleep before he woke me to say the doctor was on the phone with the news that my Dad wasn’t an empty shell. I called everyone with the good news and left a message for the girlfriend. We celebrated with bourbon-laced root beers and Italian sub sandwiches from the corner deli I picked up wearing his giant shoes like a little girl playing dress up and ate them in front of a Simpsons marathon until I fell asleep curled up in his lap on the futon. When I woke the next morning, I looked at the phone and saw that Dad’s girlfriend had never returned my call.

Brother took a week off from his job to be with Dad. He arrived at the ICU early each day and sat at the bedside talking and reading articles from The New Yorker to the motionless figure in the bed in an effort to draw him back to the land of the living. Three days later I missed my red eye out to join him and spent the night sleeping in the airport. I caught the first pre-dawn United flight out the next day only to land at O’Hare for my connection and pick up a voicemail message from a nurse telling me that my father had gone into cardiac arrest and died. I sat slumped in a chair at an electronics recharging station tucked in the back corner of Terminal 1 unable to process the news or do anything but stare at a closed hot dog stand across from me wondering whom to call first. I chose the girlfriend. I got her voicemail and hung up without leaving a message. I don’t know how many more minutes passed before the phone in my hand rang with another call from the ICU telling me that they had revived my father.

“How long was he gone? How long did you work on him?” I asked.

“Almost 20 minutes,” the nurse replied.

“Jesus. What came back? Do I even want to know?” I wondered aloud.

“Probably not,” she told me. “I’m sorry. And I have to warn you, the Medicaid counselor wants to meet with you about your Dad’s finances when you get here.”

“Great. I don’t know anything about his finances.”

“You’d better learn quick, then.”

I hung up my phone, put it away and boarded the plane without making another phone call.

I walked into Dad’s room later that morning to find my brother keeping his faithful vigil. Even in his jeans and plaid shirt with the sleeves rolled up to his elbows he looked impossibly grown up. A fresh, stalwart pillar of strength that was a sight for my sore eyes. He rolled the magazine he was reading up into his hand and unfolded his tall form to greet me with a hug. The nurse at the other side of the bed stopped fiddling with the IV pump to turn and smile at me. “Hello, Dad!” I forced myself to intone cheerfully only to be met with my father’s first movement in weeks as his head jerked immediately in my direction, his dazed, lifeless eyes searching for the origin of my voice. He wasn’t awake, but he was suddenly aware. I stopped in my tracks, dumbfounded. My brother’s face fell and he flung his arms into the air in resignation.

“Seriously?!” he asked. “I’ve been sitting here for days talking my head off to him for hours on end, and nothing. Absolutely no reaction at all from him. You walk in the door and say two words and he snaps to.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Well, at least we know somebody’s home in there,” the nurse said. “Congratulations. Nice work.”

Dad immediately returned to staring at the ceiling, like a dead, expressionless fish with the ventilator taped to the corner of his chapped mouth like a hook.

The girlfriend arrived a few hours later and was immediately threatened by the news of my father’s breakthrough with me. We decided to give her a little time alone with Dad and head to the cafeteria for a bite to eat. On our way, the nurse pulled me aside to express her concern that the girlfriend would get into my father’s face and yell at him to wake up during her visits, which was not only counterproductive for my father but disruptive to the other patients on the unit. She warned me that they might have to have her banned from visitation if it continued. I witnessed that frightening behavior firsthand when we returned from the cafeteria.

We worked to change the girlfriend’s focus and asked her for any information she might have about Dad’s finances in the face of my approaching meeting with the Medicare counselor. She claimed to know nothing, said she was going to go make a few phone calls, and then promptly left the hospital. She didn’t return our calls all weekend, which brother and I spent agonizing over the possibility that she could face financial ruin with Dad’s bills if they had mingled their accounts. When we weren’t at the hospital, we were home online looking up the laws on the subject trying to learn as much as we could. We were constantly either in rescue or research mode and completely exhausted.

The day before we were both slated to leave town, we picked up donuts for the unit staff and arrived at the hospital early to spend the morning with Dad. There was a rule limiting the number of visitors in the ICU rooms to two at a time, so we figured we’d get our few hours in with him and then let the girlfriend have the afternoon at his bedside while we did our financial homework and spent a little time with Mom. We’d called and left her a voicemail stating this plan the night before, but not long after our arrival, the girlfriend darkened the doorway and began grilling us about his condition and doing her yelling-in-his-face act again. And again, she swore she had no information about his finances and said she was insulted that we were accusing her of meddling in Dad’s accounts, which was in no way the case. It was clear that our plans for a peaceful morning with Dad were shot. We decided the girlfriend wasn’t worth the fight and that conflict in the hospital room was in no one’s best interest, so we decided to cede our ground and let her have the day with Dad. When we had arrived that morning, however, the doctor had pulled us aside to lay out the reality of the situation for us.

“We think you should know that we don’t know what’s going on with your Dad,” he told us. “We don’t know what to expect from here on out.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“This could be it,” he answered. “He’s really deep under.”

“Are you saying that he might not wake up?” brother asked. “Are you saying that this could be as good as it gets…indefinitely?”

“That’s what I’m saying.”

And so, brother and I asked the girlfriend if we could have a few moments alone with Dad to say some things we each wanted to say. We didn’t state as much directly to her, but we felt we needed to say our last words to him – just in case. Throughout the visit, each of us regularly gave the other a wide berth in this regard – one often going out to the car for something, to the lobby to make a phone call, to the cafeteria to get snacks for us both – but what we were really doing was each giving the other time alone with Dad, because we each had our own relationship with him, each had our own issues with him, each had our own things to say to him and him alone. It was an unspoken agreement that we both honored without need for discussion. All it took was a look from one to the other for one of us to just take a breeze for a little bit. No harm. No foul.

So, we expected nothing but support and understanding from the girlfriend when we politely asked if we could have a few minutes alone with Dad to say our goodbyes before leaving town. Instead, she angrily huffed out of the room. We didn’t think much of it because such behavior was getting to be commonplace from her, so we spoke our piece and then went to the lounge to look for her. She wasn’t there. She wasn’t in the lobby. She wasn’t in the cafeteria or chapel. She didn’t answer her phone. We shrugged it off and went home, sad and exhausted. We didn’t say much else to each other for the rest of the day, and we never heard back from the girlfriend.

The following morning, brother drove me to the airport on the way out of town. The atmosphere in the car was heavy and tense. He reached over and squeezed my hand as I stared out the window, incredibly uncomfortable with the fact that we were leaving with Dad still in a coma. We both had jobs to get back to, and I had a dying cat who was in fast decline waiting for me at home, but none of that mattered. We were taking off with nothing to show for our visit except bad news and stress. We had gotten nowhere and there was no end to nowhere in sight. He pulled up to the curb. We stepped around to the tailgate. He pulled my suitcase out of the truck bed and extended the handle. He hugged me. Gave me a kiss and a reassuring squeeze. I told him I loved him. He replied in kind. I headed into the terminal. When I boarded the plane, I followed what had become my standard operating procedure and called the ICU before they closed the doors to let them know that I’d be out of reach for the next couple of hours and gave a blanket pre-approval for any procedures that Dad might need while I was in flight. A nurse named Kenny answered the phone.

“Wait. You’re leaving?!” he said.

“Yep. On the plane getting ready to take off as we speak,” I replied.

“Oh my God. No one told you?!”

“Told me what?”

“Your Dad is awake.”

“What the hell? Are you kidding me?! Why didn’t anyone call us?”

“His girlfriend was here. She said she was going to call you. That was over an hour ago. We thought you knew! We thought you were on your way in here!”

“No. No one called us. Where is she now?!”

“We don’t know. She just came in, saw he was awake, said she wanted to be the one to call you and walked out the door. We haven’t seen her since.”

“So, you’re saying my Dad is awake and alone? No one is with him?!”

“Yeah. He’s awake and alone. And he’s pretty confused. You’d better get in here.”

“Godammit. I have to go. I’m sorry Kenny. I have to go fix this. I have to get off of this plane.”

I tried to get up and get off the plane, but the doors had shut and we were starting to taxi to the runway. The stewardess told me to sit down. I opened my phone and dialed my brother.

“Ma’am. I need to you turn off your phone and put it away. The airplane doors are closed.”

“Yeah, I get that, but I have to make this phone call.”

“Ma’am. Turn off your phone.”

“I will. After this call.”

“Now. Turn it off.”

“No. You can throw me off this plane if you like. That will only be doing me a favor, but the only way I’m turning off this phone before making this call is if you get the TSA on board and arrest me. Your move. Now, if you’ll excuse me…”

I made the call and reached brother right away. I explained what happened. He immediately turned his truck around and drove back to Dad’s hospital room. When he got there, there was still no sign of the girlfriend. He settled into the chair next to Dad’s bed and held his hand. Dad was awake, but his mind was a storm, and he was in a frightened limbo.

The flight to Dulles was less than an hour but felt like an eternity. The moment the plane was on the ground, I had my phone powered back up and started making phone calls. My first was to the girlfriend. Again, I received no answer, so I left a voicemail detailing the situation and asking her to call back and explain her side of things. I wanted to know where she was and why she hadn’t called brother and me to tell us why Dad was awake. As soon as I got off the jetway, I collapsed into that chair in Concourse C and called brother. I asked him what I needed to do. If I needed to get back on another plane and go back to the hospital. He reminded me that I would be lucky to get a flight out to anywhere in the DC snowstorm. He laughed when I suggested renting a car and driving through it back to him. I knew he couldn’t stay there. Knew Dad would be left alone soon. Knew Dad responded to my voice. And yet, I didn’t know what to do. He held the phone up to Dad’s ear to let me talk to him, and then told me Dad was looking around for me. All I could hear were increasingly agitated grunts and whines on the other end of the line and alarms going off on the machines monitoring his vitals.

“What should I do?” I asked my brother.

“I don’t know. I don’t know what to do here at all. He’s awake, but he’s not,” he replied. “Here, talk to Kenny.”

Kenny talked me down off of the ledge. Assured me that what Dad needed was some quiet time to come around. That I needed to go home and take care of my business and let them take care of Dad. That it was ok for both brother and me to head home. They’d have our backs. Nonetheless, I sat there in agony with my face in my hands, breaking apart and trying not to bawl my eyes out in public. Felt panicked and caged and furious. Knew we’d been betrayed. I boarded my flight back west, and by the time I landed four hours later, I was seething. By the time I listened to the girlfriend’s voicemail explaining that she purposefully had not called us to let us know that Dad was awake as petty payback for excluding her from our goodbyes to our father and as insurance that we would indeed leave town and stop poking around in his financial affairs, I was in a full-tilt murderous rage. I was ready to get on a plane and fly back east with the express purpose of stabbing that stupid bitch straight through her baggy, wrinkled neck just to watch her bleed out on my shoes before kicking her lifeless body down the stairs and out into the street so I could back over it with my car twenty times before roadhauling her broken corpse to the bay and throwing what was left of it into the briny deep to be some bottom feeder’s dinner. My wrath was off the charts – inhuman — and it was a good thing that thousands of miles separated us, or I would be doing hard time for first-degree homicide right now and wouldn’t regret my actions one teensy bit. I was in a dark, dark place and capable of black, black things. Instead, I cooled down and gave her the pimpslapping of her life in an email that reminded her that I was in charge – so very much so that I could yank visitation privileges and set legal action into motion – and she fell back in line. Or so I thought.

One month later, I discovered that she’d gotten the better of me and started emptying tens of thousands of dollars out of my father’s bank accounts (the joint accounts with my name on them) within hours of his accident. At that point, all bets were off. I peeled off the gloves, lawyered up and spent the next year kicking her ass all over the court system first as my father’s conservator and later as the administrator of his estate. She sued me. I threatened to sue her ass right back. I kept her out of the hospital so my Dad could die in peace with his family. I fought tooth and nail and got the money back and got her out of our lives for good, and I did whatever it took to get there. I lost sleep. I lost my livelihood. I lost friends and relationships. I lost countless hours I could have spent with my father in his last days instead meeting with lawyers and bankers in an effort to do my court-appointed duty – a duty that was only made necessary by her theft. If she had not been in the picture, there would have been no pressure to be away from my father. I am only grateful that my brother was able to be there with him when I was not. Two heads were better than one. But after five to seven hours of sitting in banks and law offices each day, I would go and spend another five at the hospital taking care of Dad, helping him to get off the ventilator and speak again, feeding tiny sponges of water into his parched mouth for him to suck on so he could slake his thirst without choking, suctioning the tracheotomy hole in his throat, massaging his hands that had been balled up in giant mitts that kept him from pulling out his feeding tube, cutting his toenails and scraping thick, dead skin off of his feet, giving him sponge baths, cleaning up his shit from the bed, and helping the nurses change his sheets all while making pleasant conversation about college basketball or any other topic that had nothing to do with his dire situation or the drama with his finances and his girlfriend. There was no need to stress him when he needed all his strength to get well. Why bother when I was using all of my strength to fight the rest of the battles for him?

In the end, I won. The girlfriend signed the papers, tucked tail, and ran away broke and in ruins. She would occasionally show up at my bank and make threats and a scene shouting about her impending marriage to some new beau only to have them call the cops on her. She would call my lawyer and try to intimidate him with promises of new lawsuits, but he only hung up on her. She eventually gave up and went away.

In the end, I lost. The girlfriend made my father’s death so much harder for me. Fighting her while fighting to keep my father safe cost me my energy, health, and well-being. And, for a large part, my sanity. I was never a bright and happy-go-lucky little soul, but I discovered darkness and depths I didn’t think I had, much less could sink to. I had to live in anger and hate and at a state of constant battle-readiness to deal with her. I had to be constantly ugly and hard and conniving and one step ahead. It was war. I was manic. I was on edge. I was gritty. I was spiteful. I was sharp. I never, ever let up. I was fucking scary. I was not able to grieve until the fight was over and I could lay down my sword knowing the job was done, that I no longer had to protect my family from an outsider who had no business complicating our lives in the first place. When I was finally done exploding and the dust settled, I found that I was no longer me. I was irreparably changed. Infinitely spent.

When a star reaches the end of its life, it goes supernova, destroying everything around it and, ultimately, itself. In the aftermath, one of two things can happen to it. It can become a super dense neutron star that eventually collapses onto itself to become a black hole that sucks everything, including light, into its gravity well with no hope of escape, or it can lose most of its mass and become a very small, very hot white dwarf. A white dwarf continues to burn intensely, giving off a great deal of heat as it quickly spends the last of its fuel, but it is a shrunken shadow of its former self that gives off precious little light compared to how it used to shine. It’s still warm and breathing, but its days of giving life and leading the way are over. Eventually, it burns out and becomes a cold, dark rock – a black dwarf – that just floats alone and useless in space.

When a beloved mentor of mine died at the start of 2009, a dear friend sent me a sympathy card that I still treasure. It had an old Japanese proverb on the front: fall down seven times, stand up eight. After Dad died, I spent nearly two years piecing myself back together, with varying results. While arguably my biggest and most taxing loss, he was hardly my only. I lost 16 people and an animal companion in the past four years. Each time, I pulled out my friend’s card and looked at it and got back up for more. Each time a little wobblier, a little more blurred in the vision and unsure of my footing. Landing fewer and fewer blows each round just waiting for the bell to send me back to my corner so I could just. sit. the. fuck. down. for a minute. Eventually, I fell down eight times twice over. I don’t know how I kept getting up.

I’ve battled depression. Wrestled it for most of my first thirty years. I spent four years on meds and the therapist’s couch doing the hard work necessarily to finally get the drop on it and figure out how to manage it. I’ve had a few flare ups since then, but I never lost the high ground on that demon. I know all her moves now, and I can anticipate and out-maneuver her pretty easily. Now, no offense to others battling that very real and very horrible and very dangerous affliction, but grief makes depression look like a case of the sniffles.

If depression is a demon, grief is fucking Cthulhu. Grief snaps depression over its knee, eats it for breakfast, calls for seconds, and then demands to know what’s for lunch. Depression is a soft little black cloud or blanket-like companion that follows you around and gently and gradually insinuates itself into your life until it’s wrapped so snuggly around you it’s all you know to the point of altering your reality. It becomes a part of you, and comparatively, it’s a spa vacation.

Grief is the jackbooted thug that suddenly breaks down your door, grabs you by the throat and rips you from your bed, your life, and your sanity. It kicks and beats you mercilessly until your insides are nothing but bloody soup and then throws you into the mud, grinds its heel into your neck, and holds you down with your face in the filth as it brutally rapes you repeatedly on a daily basis in full view of the family and friends who stand watching on the edges of the normal and happy life you used to have. Grief remains an external force. You can tell the difference. You can still see the world going on around you, know the sun is shining but that you are no longer part of it no matter how much you miss it. You know you’re a hostage, and your captor will either Stockholm syndrome you into accepting him as your new reality or just break you entirely. He doesn’t care which. Fighting it is futile. He likes it when you struggle. It gives him satisfaction, a reason to taunt you. Makes it better for him. He just laughs at any of your attempts to get away as he jerks you from the sound sleep you desperately need well before dawn with a quick intake of breath, a shock of adrenaline, and opens floodgates to the reality of your loss that rushes in to fill the space you thought you’d reclaimed in dreams where your loved ones are still with you in places where you were once happy and whole. Grief starts your day with trauma. Rips off the scab to reopen the gaping wound, and then shoves you out the door into the light to watch you stumble through your day bleeding all the while and then places bets as to whether or not you’ll collapse completely before the sun goes down. It doesn’t like your odds and roots for you to fail. And then it does it all over again the next day. And the next. And the next. And the next…

But I’m a survivor, see? I got away. I started this year with the determination that my grieving days were over. That I was going to hold my head high, smile a smile – even if it was a slightly deranged one – and be happy and free again. And I did a pretty good job of it. Even if I have been letting some things slide on the backside, up front, I’ve felt better and lighter than I ever have. I’ve been ignoring the fact that I’m no longer the person I used to be in many ways and just choosing to enjoy myself. It’s come at a price, though. I’m more placid and pliant than I’ve ever been. I’m less responsible. I’m needier and more selfish. I voice my desires, ask for what I want without shame and usually get it. And it feels better to have someone hold me. Feels better to have space when I want it. Feels better to breathe deep in the sunlight. I don’t try to hold onto anything anymore, because it’s just going to go away anyway. I can only worry about me, and even then I don’t care that much. Not only do I have no fight in me anymore, but I’m absolutely tame — almost to the point of being helpless mush. I let most things wash over me. I’m happy to let others decide for me, tell me what to do, even lead my around by the nose. Even when I should fight back, I often don’t. It takes a great deal to get my hackles up, and even then, my heart’s not in it. I don’t just pick my battles, I rarely fight any of them at all, which is odd, given the fact that I used to fight others’ fights for them and then go out picking some more of my own. Now, I wander more or less aimlessly. I let others make the plans, decide where I’m going to go when, choose what I eat, dress me, undress me. I stand there docile and smiling, my glazed-over eyes watching things – even my clothes – slip onto me and fall away at others’ will. Because, really, what difference does it make if I’m happy and nothing hurts anymore? I beat my swords into plowshares. I’m retired. Others can make the hard decisions now. I’m not going to make any at all – not even for myself. I’ve seen the in-charge version of me, and she’s an instrument of torture — the embodiment of self-harm. She hurts me. I’m tired, and I don’t want to have to think about the hard and dark things anymore. I paid my dues and then some. I’ve cashed in my chips. I’m done. I’m just over here being a small, warm star giving off as little light as possible and enjoying my new, downgraded status immensely.

And so, as I walked through Dulles and passed the chairs in Concourse D, I paused and looked at my ghost. I could see her sitting there in her boots and jeans and down vest curled into a ball with her face in her hands and her head between her knees in an effort to calm her breathing and forgo passing out from the pressure and pain. Watched her struggle with rage and indecision trying to figure out how to be the Best Daughter She Could Possibly Be. Making battle plans. Donning her armor and moving her armies into position. I could see her swallowing it all, shoving herself down, and bracing herself for an impact that was still months – years in coming. Witnessed the very moment she moved from damage control to force of nature, switched from defense to offense and hurtled herself over the cliff. And she looked so wan and sad and small. I felt sorry for her. I was sickened by her. I wanted to hold her tight and stab her to death simultaneously. And I couldn’t help but feel shocked by the contrast. There I stood in my light cotton summer dress and sandals, feeling tall and light and carrying almost no literal or figurative baggage, breezing through the airport on my way home from a fun vacation abroad. Traveling by choice and for myself. Only answering my own call – my greatest concern being finding the Auntie Anne’s and getting a yummy pretzel and some lemonade. I felt like a completely different person. Looked at my ghost like she was a dream I’d once had as she faded to nothing and I turned away and bounced down the carpet toward my gate and my flight home giddy with gratitude that all the pain was behind me.

Or so I thought.

My mother’s dormant heart condition flared a few months ago, and her condition worsened exponentially while I was overseas. Within days of my return home, she couldn’t manage enough breath to carry on a phone conversation with me. She was on leave from work and at home struggling to get her vitals under control with medications that weren’t doing the job. She spent July 4th in the emergency room only to be sent home with more medications that didn’t help. The following morning, her neighbor called 911, and an ambulance spirited her back to the hospital, where she spent several days. My brother was immediately on a plane here to meet up and fly together out to be with her. We had gone through this with her 6-7 years ago and thought the ablation she’d had back then had put the genie back in the bottle. The fact that this beast was back scared us, and we knew it wasn’t something we could wait out, especially with talk from the doctors of impending cardiac procedures.

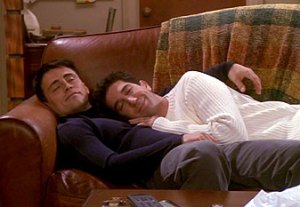

I was immediately reassured to see him standing on the curb at the airport waiting for me to swing up and collect him for a night at my house before we flew east together the next morning. Tall and solid and capable, he greeted me with a tight hug and readiness to be my teammate again in Operation Take Care of Sick Parent. Having a sibling who has your back makes the hard times so much easier. Even traveling together, we quickly fell into our same old familiar pattern, dividing the labor of getting packed, planed, and to the hospital without even having to discuss much. We each know our roles, and we can communicate our next moves with a simple look. It felt good to slip into the plane seat next to his, order our bourbons, fire up his laptop, each take an earbud from my headphones and get lost in season 3 of The Venture Brothers together for a few hours. I just leaned into his strong shoulder, basked in his warm laughter, and felt supported amidst the chaos. Secure against my genetic other half – the only person with whom I never have to try, the only person with an equal investment in our family, the only person I trust to get it done, the only person as scared as I am. In many ways, he is my family entire sometimes, because I know that, in the end, we will be the last ones standing and that he needs me to be there as much as I need him.

Brother gets me like no one else. Not all of me – in fact, most of me leaves him shaking his head, I think – but he knows me, knows what to expect even if he doesn’t always agree or know the whys and hows. But he’s got the institutional history. He’s the only one who was there for the backstory. He’s the only one tapped into the same frequency. We know each other’s strengths and weaknesses, know how to operate in a way that covers our flanks in a crisis. We perfected our teamwork with Dad, and when we’d heard from Mom that she’d written up her legal plans to put him in the lead as the medical power of attorney rather than me, we both freaked out. Mom’s concern that I had already carried that weight with Dad was valid, but what she didn’t understand was that brother and I had come to an agreement about what worked for the two of us and agreed that that job was mine. Not only is it the only one I can do, but I have an uncanny predisposition for managing the big picture of a situation and understanding and tracking medical information. I have dealing with doctors and hospitals down to an art and grasp the medications and procedures with expert aplomb. I’m the front line. The faceman. The starring lead. While usually the pathos to brother’s logos, I have a disposition that allows me to set everyone’s emotions aside and gather and process all the information needed to make the tough decisions in a medical crisis. I have a robotic emergency mode, and it came right back to the fore the moment Mom’s problem began. I almost felt bad at times when I had to tough love her long enough to get the necessary information down on paper before I could let anyone’s feelings – even hers – enter in to the picture. I go full-on taskmaster, and it’s kind of scary, but it’s what needs to be done. That’s just it, I do what needs to be done, and brother knows I do it well. Whereas I know what he does well is EVERYTHING else in a way I cannot. He is the logistics man. He keeps the eye on the clock and remembers who is where and what needs to be done when. He’s the one to keeps the files and packs everything up and gets us to and from the hospital. He’s the wheelman who runs us to the drug store, the grocery store, you name it. He’s the morale officer who always has a joke ready and makes sure I take time for a little mental recreation with him at the end of each day. He’s my handler — he makes sure I get up, get dressed, eat, and get in the car every day – all on time. He’s the one who ensures I’m where I need to be to talk to whomever I need to talk to and then makes sure I get home and in bed again. He handles all the hundreds of little details and takes care of me (and keeps me laughing) so I can handle the few big things and not be cluttered with anything else. I’m like this thing he wheels around and props up and hits a switch on, and when the show is over, he powers me down to conserve my batteries, packs me up in my little box, and puts me back away until I’m needed again. It’s a weird little process, but it works for us, and we convinced Mom that our system was how it needed to be. As hard as it would be to do all over again, to alter our operation in any way would only create more stress for us than it would avoid.

This time was different, though. Brother did all the heavy lifting. When he unpacked me and propped me up to do my thing, my batteries were dead. I mostly just stood there spinning my wheels. I stared off into space. I was prone to fits of punch-drunk giggles. I was more morale officer for Mom than medical expert. I was still the faceman, but man, did I not put my best face forward. I was phoning it in while brother was stepping up. I felt like I was moving in molasses, outside of my body watching the scene unfold – a scene where I was mostly just sitting there until brother would come over and physically lift me up out of the chair and get me moving. It was bizarre and surreal to feel so ineffectual. Granted, I was endlessly impressed by how capable brother was. He truly manned up and took expert care of Mom – but he was also taking expert care of me. I was baffled by what was happening until he went home and left me with Mom.

On the day he left, I found myself standing in my mother’s little walk-in bedroom closet looking for a photo album. As I looked around me, I realized that Mom had more possessions in that closet alone that Dad left behind in the sum total of his estate. While Dad went out with a bang that was rife with tragedy and mess and gut-wrenching existential decisions and a messy legal battle that all brought me to my knees, he had no stuff. In the end, his whole life fit in the back of brother’s little Ford pick-up. There was no memorial. He had no friends, and with the exception of his lone brother in Los Angeles, all of his family was dead save for brother and me. We cremated him and settled the finances of the estate and the lawsuits and that was that. Chapter closed. We grieved quietly on our own terms and alone. Standing there in the closet, the full enormity of Mom bore down onto me. For as close as I was to Dad, Dad was a difficult person to love – only I really found a way to do it. Mom, on the other hand, is our everything. She’s the parent who stuck with us, the one we love most. Our friend. Our rock. Our alpha and omega. Our rod and staff. She’s home, and we love her immensely – and so do countless other people. She has a career. She has extended family. She has innumerable friends – some of whom have known her since childhood. Mom’s life is full, as is her home. Her house is a special place – a refuge for us. It’s a modest townhouse, but every room is nothing but her personal touches of décor and decoration, all hand-chosen by Mom and a comforting reflection of her.

When we lose her, not only are we going to be devastated by the most difficult loss of our lives, but we’re going to have to share it with others who we will have to notify and comfort all while having to dismantle our family home – the physical manifestation of who she was and who we all were together. We’ll have to shut down our base of operations and finally work without a net. We’ll have to give away parts of her and then pack up and go home without her. We’ll be orphans. We’ll be on our own. We’ll be wrung out and wasted and lost.

And I realized I wasn’t ready. I will never be ready to lose Mom, but I’m really not ready now. I’m all out of fuel. I spent it all on Dad, and I haven’t recharged. Maybe I never will, and that scares me, because if any family member deserves 110% from me, it’s Mom, and I’m going to fail her. I’m already failing her. I’m distant. I’m pulling away so I won’t feel it. Like it will hurt less somehow when it actually happens if I detach and put some space between us. And really, who am I kidding with that? But there I stood in that closet as the walls closed in on me. I panicked. I opened my mouth to scream, but nothing came out. I just doubled over with my mouth hanging open and panted and hyperventilated in silence – back to being that same girl in the airport on that winter’s day. The light, free, happy girl in the sundress shattered and flew apart and completely dissipated. She only existed for six short months. And here I am, right back under grief’s boot heel preemptively. Aware of how terrified Mom is. Aware of how terrified I am. Aware that any goodbye could be our last. Painfully aware that I left Mom to weather a procedure and get a painful diagnosis alone this week when I should have been at her side – I was just too tired and weak to do my job. I’m already wrenched from sleep with that shocking kick to the gut every morning. I get that brief moment of confusion before the reality of what’s happening comes rushing back into my mind. The reality that Mom is in heart failure. The reality that I’m not able to be there for her like I should be. The reality that I’m going to fuck this up. The reality that I already am. Try as I might to pace myself for the long run, I’ve already blown my wad, and Mom deserves better. When (not if) the decline happens, I will be worthless. I swam out too far and didn’t save anything for the trip back. I’m stranded at sea and no good to anyone.

Everyone’s watching me from the corner of their eyes. They know that something’s wrong. They don’t know what it is, but they don’t trust me. Mom and brother are especially concerned — treating me like I’m fragile. Taking care of me. Waiting for me to crack. Only one person on the planet has any clue about how bad it really is. She’s the only one I can trust with it. It’s kind of her job to know these things. She’s known me so long, and she gets it. She knows how awful I am, and yet she still loves me. Even with her own burdens, she gladly piles mine onto the pile and carries them. I just can’t explain this over and over. I won’t go into details. Don’t know how to tell everyone that the fight has gone out of me. That I’m already dead inside and just going through the motions. That what I’d gained this year — my comeback — has so quickly slipped from my grasp. That I’m grief’s bitch yet again, and probably for good. I know this feeling all too well, and I’m just relenting to it. Sometimes the devil you know is easier. He’s won. Swept my legs out from under me and scrambled my guts. I want to scream all the time and nothing comes out. I’m so tired, and I just want to sleep. I’m on ropes and slipping fast – and now when it looks like my family will need me most.

I’m trying to dig deep. Trying to get it together, but I’m so tapped out. I am in a place where I can’t even take care of myself much less anyone else. Much less the woman who needs me most. I just want to be left alone to curl up in a ball and be quiet. The storm’s coming, and I can’t stand out in it again. There’s no substance to me anymore. I’ll just blow away. I still have my first dead parent’s ashes sitting on a shelf in my bedroom. Dad’s not even scattered, and now Mom’s sick. I turn 40 tomorrow, and I’m not ready to lose my favorite parent, the only one I have left. Especially when I just got her back. Especially when I know I don’t have what it takes to save her. The test isn’t even here yet, and I’ve already failed. I’m not even a dim little star with a last burst of heat to tap. I’m already the black dwarf — all bled out. The cold, dark rock floating alone through space with no heat or light for anyone.

There was an item in the news this week that the universe won’t end with a bang or a whimper but rather a giant rip. That, thanks to dark energy, ironically enough, it will continue to expand to the point where everything just flies apart. Stars, planets — even the atoms — won’t be able to hold together any longer. Everything will stretch to the breaking point, and then it will shatter and come apart completely and dissolve into nothingness. All known existence will violently rend itself asunder, and faster than expected, it seems. The world will simply spread itself too thin. This is how things come undone and have their ending.

I can relate.

He laughed under his breath because you thought that you could outrun sorrow

He laughed under his breath because you thought that you could outrun sorrow